Orion is proud to partner with BBC Sky at Night Magazine, the UK's biggest selling astronomy periodical, to bring you this article as part of an ongoing series to provide valuable content to our customers. Check back each month for exciting articles from renowned amateur astronomers, practical observing tutorials, and much more!

Orion is proud to partner with BBC Sky at Night Magazine, the UK's biggest selling astronomy periodical, to bring you this article as part of an ongoing series to provide valuable content to our customers. Check back each month for exciting articles from renowned amateur astronomers, practical observing tutorials, and much more!

Voyager: The 40-Year Space Journey

In 1977, two spacecraft left Earth to explore the gas and ice giants. On the anniversary of their departure, Jenny Winder charts their journey towards the edge of the Solar System

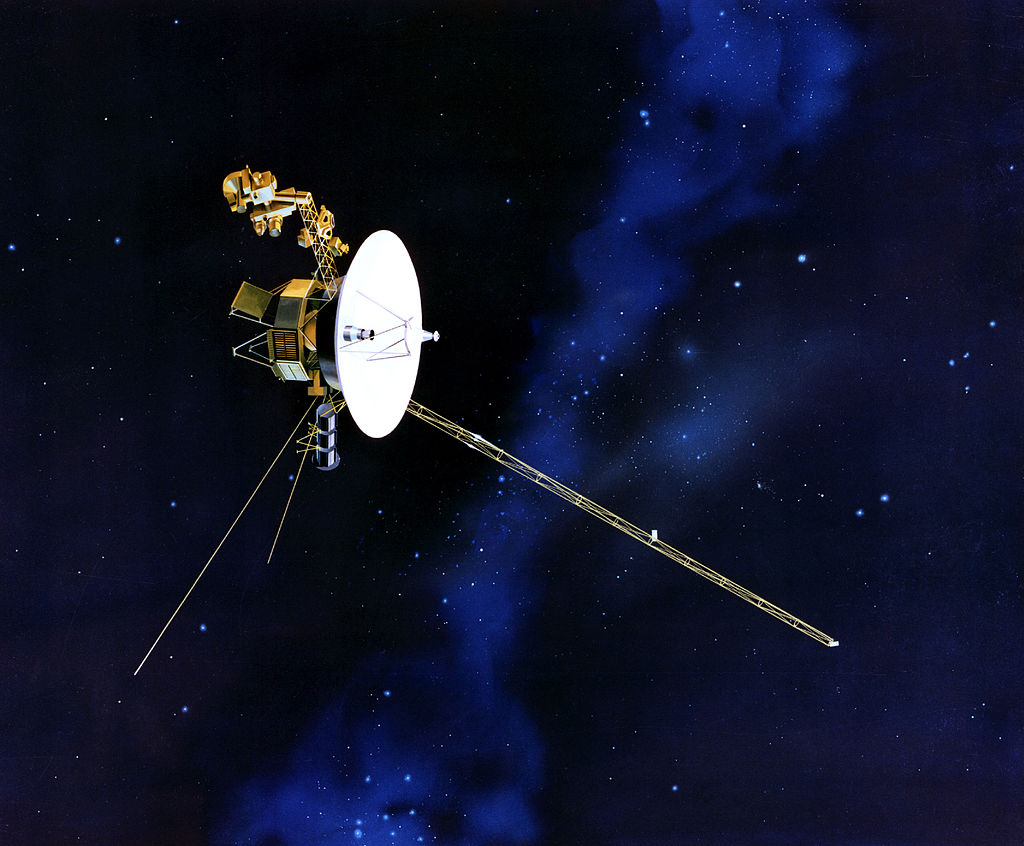

Artist's concept of Voyager in flight. By NASA/JPL [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Forty years ago, in August and September 1977, NASA launched two spacecraft on an audacious mission that would eventually study all four giant outer planets and 48 of their moons, and go on to explore the outer reaches of our Solar System. Today, Voyager 1 is our most distant spacecraft, and in 2012 became the first to enter interstellar space. Voyager 2 isn't far behind; it's hoped that it too will 'go interstellar' in the next five years.

The origins of the mission hark back to 1965, when it was realised that a planetary alignment in the latter half of the 1970s would enable a spacecraft to make a complete survey of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. Such an alignment only occurs every 175 years — it was an opportunity not to be missed.

To make the most of it, NASA settled on two identical spacecraft to travel on two separate trajectories. Both would study Jupiter and Saturn. Voyager 1 would then go on to fly by Saturn's largest moon Titan. Voyager 2, meanwhile, would have the option to go to Uranus and Neptune, becoming the first spacecraft to visit either. Each planetary flyby would alter the spacecraft's flight path to deliver it onto the next planet and increase its velocity, reducing the flight time to Neptune from 30 years to just 12. Pluto was off the table; the choice was between it and Titan, and Titan was seen as a more interesting target.

Budget constraints meant the spacecraft were officially only built to last five years, with the hope that they would be able to complete the extended mission to Uranus and Neptune. They launched with 11 scientific instruments: four on Voyager 1 continue to send back data about its surroundings, while five remain operational on Voyager 2.

One of the instruments still active on both is the low-energy charged particle detector (LECP) instrument, which scans the sky through 360° every few tens of seconds measuring cosmic rays. That it continues to function is extraordinary, says its principal investigator, Dr Stamatios M Krimigis.

"The most remarkable design feature of LECP was the stepper motor," he says. "A mechanical device like this in space was frowned upon because everyone thought it could get stuck in short order. We tested the motor for about 500,000 steps, twice the expected usage and it survived. Now it's performed over seven million steps and counting."

Science data from the instruments is returned to Earth in real time via each probe's high-gain antenna. The signals are picked up by the Deep Space Network (DSN), a global spacecraft tracking system, which was also used to reprogram the spacecraft remotely on more than one occasion. Travelling too far from the Sun for solar panels to be employed, the probes rely on three radioisotope thermoelectric generators for power. These convert heat produced from the radioactive decay of plutonium into electricity.

Messages for ET

Each spacecraft also carries a message from humanity in the form of a 12-inch gold-plated copper record. The cover for the Golden Records bear diagrams explaining how to play them, showing the location of our Sun and the two lowest states of the hydrogen atom as a fundamental clock reference.

The selection of content for the record, by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan, was completed in six weeks, chosen to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth. There are spoken greetings in 55 languages; 116 images; recordings of natural sounds; music from Bach, a Navajo Indian song, Azerbaijani folk music and Chuck Berry; and even a recording of the brainwaves of Ann Druyan, the creative director of the project.

Voyager 1 was launched two weeks after Voyager 2, but on a shorter and faster trajectory that would see it overtake its twin and reach Jupiter first. Between January and August 1979, the Voyagers studied the Jovian system. They revealed Jupiter's famous Great Red Spot to be a complex anticyclonic storm, found smaller storms throughout the planet's clouds and saw flashes of lightning in the atmosphere on the night side. Jupiter's faint, dusty rings were also discovered, along with the satellites Adrastea, Metis and Thebe. But the highlight of the Jupiter mission was the discovery of active volcanism on the moon Io. Together, the Voyagers observed the eruption of no fewer than nine volcanoes on Io. "At that time, the only known active volcanoes in the Solar System were here on Earth, and here was a moon, just a moon of Jupiter, that had 10 times more volcanic activity than here on Earth," explains Voyager project scientist Ed Stone, who has been with the mission from the start. The Voyagers also found Io was shedding a thick torus of ionised sulphur and oxygen, and revealed evidence for an ocean beneath the icy crust of Jupiter's moon Europa.

At Saturn, they studied the planet's complex rings and its atmosphere, and found aurorae at polar latitudes and aurora-like emissions of ultraviolet hydrogen at mid latitudes. They measured Titan's mass, studied its thick nitrogen atmosphere and imaged 17 of Saturn's moons, including three new discoveries: Atlas, Prometheus and Pandora.

From there the two probes parted company as Voyager 1 began its long journey out of the Solar System. Voyager 2 headed to Uranus, where it discovered 11 new moons and visited 16. It discovered the planet's magnetic field and studied the ring system. At Neptune Voyager 2 discovered storms, including the Great Dark Spot, and 1,600km/h winds — the strongest on any planet. It imaged eight of Neptune's moons, discovering five of them and saw active geysers on the largest moon, Triton.

One last glimpse

On Valentine's Day 1990, Voyager 1 took the final pictures of the mission. Turning its camera back towards the Sun, from about 6 billion km away, it took images of Neptune, Uranus, Saturn, Jupiter, Venus and — suspended in a beam of sunlight — the now famous 'Pale Blue Dot' image of Earth. Carolyn Porco planned and executed this Family Portrait alongside Carl Sagan. "As soon as I joined the Voyager imaging team in fall 1983, the idea arose in my mind to take an image of the planets, but especially Earth, as they would be seen from far away, to force that 'reckoning' that comes from seeing our cosmic place as it really is ... alone and isolated," she says.

This marked the end of the Voyagers' planetary explorations — the Grand Tour, as it's known — and the beginning of the Interstellar Mission. In 1998, Voyager 1 overtook Pioneer 10 to become the most distant spacecraft from the Sun. Voyager 2 is expected to pass Pioneer 10 by April 2019.

In December 2004, Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock, marked by a massive drop in particles detected from the Sun and a rise in cosmic ray particles. Voyager 2 followed in August 2007. Finally, on 25 August 2012, at 121 AU from the Sun, Voyager 1 officially crossed into interstellar space.

The Voyager team is still listening. "We listen every day, for four to eight hours per day, per spacecraft, and we'll continue to do that as long as they are sending us something new to learn," explains Ed Stone. From 2020, however, the remaining instruments will be switched off one by one to conserve power. It's hoped they will fly for at least 10 more years. "My goal is to have a 50th anniversary party for Voyager," says Suzanne Dodd, project manager of the Voyager Interstellar Mission.

Stone considers the Voyagers to be "our silent ambassadors". In 40,000 years, they will each pass 1.5 lightyears from stars in Andromeda and Camelopardalis. Having increased our knowledge of our solar neighborhood, the Voyagers will take the story of Earth on to other star systems.

Voyager Mission Timeline

On their long travels, the Voyagers visited four planets and imaged 48 moons. Now they are at the very edge of the Solar System.

20 August 1977

Voyager 2 launches from Cape Canaveral at 14:29 UT atop a Titan IIIE-Centaur launch vehicle

5 September 1977

Voyager 1 launches at 12:56 UT from Cape Canaveral also atop a Titan IIIE-Centaur

10 December 1977

Voyager 2 enters the asteroid belt, swiftly followed by Voyager 1

19 December 1977

Voyager 1 overtakes its twin, placing it on course to reach Jupiter first

8 September 1978

Voyager 1 exits the asteroid belt and continues on to Jupiter

21 October 1978

On a slower trajectory, Voyager 2 finally exits the asteroid belt

5 March 1979

Voyager 1 makes its closest approach to Jupiter

9 July 1979

Voyager 2 makes its closest approach to Jupiter

12 November 1980

Voyager 1 flies by Titan and Saturn, then begins its journey out of the Solar System

25 August 1981

Voyager 2 flies by Saturn but remains within the plane of the planets, bound for Uranus

24 January 1986

Voyager 2 has the first-ever encounter with Uranus, revealing a bland visible surface

25 August 1989

Voyager 2 is the first probe to observe Neptune, a stormier planet than its neighbor

14 February 1990

Voyager 1 takes the Pale Blue Dot image of Earth from 6 billion km away

17 February 1998

Voyager 1 becomes the most distant human-made object in space

17 December 2004

Voyager 1 passes the termination shock and enters the heliosheath

30 August 2007

Voyager 2 passes the termination shock and enters the heliosheath

25 August 2012

Voyager 1 crosses the heliopause and enters interstellar space

Copyright © Immediate Media. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical without permission from the publisher.