Orion is proud to partner with BBC Sky at Night Magazine, the UK's biggest selling astronomy periodical, to bring you this article as part of an ongoing series to provide valuable content to our customers. Check back each month for exciting articles from renowned amateur astronomers, practical observing tutorials, and much more!

Orion is proud to partner with BBC Sky at Night Magazine, the UK's biggest selling astronomy periodical, to bring you this article as part of an ongoing series to provide valuable content to our customers. Check back each month for exciting articles from renowned amateur astronomers, practical observing tutorials, and much more!

Returning to Venus

Space Probes have helped us build a good picture of Mars, yet Earth's inner neighbor Venus is still very much a mystery. But, writes Paul Sutherland, a host of new missions are being planned to help us learn more about it.

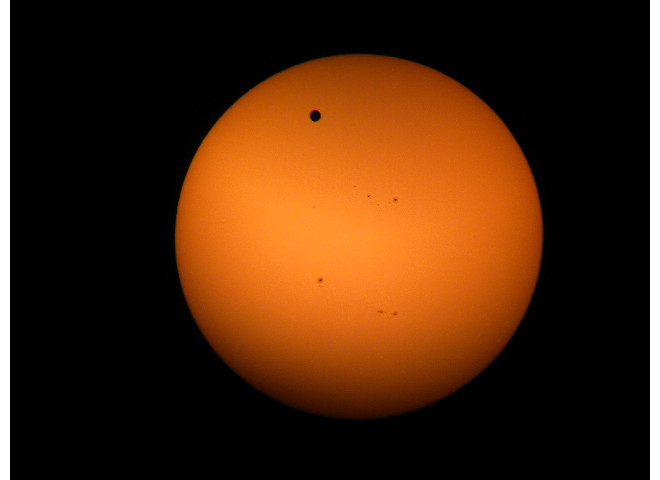

Image by Anna M., Venus Transit

Nothing was known about the surface of Venus before the Space Age because it is completely obscured by clouds. Scientists once speculated that it might be a raging ocean, or a Sahara-like desert. The first probe to provide answers was NASA's Mariner 2, which flew past Venus in December 1962, discovering that surface temperatures must be extremely high and that, like Uranus, it rotates in the opposite direction to the rest of the planets in the Solar System. Since then, orbiting probes with cloud-piercing radar have produced maps of Venus's surface and Soviet landers have confirmed that conditions are completely inhospitable on the ground. There is neither sea nor desert, but rather a landscape resembling a vision of hell.

Fire and Brimstone

The surface temperature is twice the maximum found in a kitchen oven and the pressure of the poisonous atmosphere is 90 times that at sea level on Earth, which crushed probes making early landing attempts. The first Soviet probe to reach the surface and send back signals was Venera 7 in 1970, which survived for 23 minutes. It was followed by the more successful Venera 8 in 1972, which returned data on the surface temperature and pressure, wind speed and illumination, before being destroyed after 63 minutes. The probes had to be built like submersibles to withstand the air pressure, but their electronics quickly failed in the extreme heat. Subsequent Soviet landers in the 1970s and 1980s sent back crude photos of a rocky landscape.

Helium balloons were released into Venus's higher, cooler atmosphere in June 1985 by two Soviet Vega probes that were on their way to Halley's Comet. They gathered data for 47 hours each as they floated 50km high in the cooler clouds.

NASA's Mariner 10 flew past Venus in 1974 en route to Mercury and managed to image wind patterns in the clouds. This was followed by a dedicated US mission, Pioneer Venus, made up of two spacecraft that arrived in December 1978. An orbiter studied the atmosphere and made radar maps of the surface. The other component was a multiprobe made up of a transporter and four separate probes that were fired into the atmosphere, returning data for an hour.

NASA's next mission, Magellan, carried out extensive radar imaging of Venus from a polar orbit in the early 1990s. Its imaging of almost the entire surface revealed it was covered with volcanoes. Scientists suspect many are still active, but still no one can say for certain.

ESA's first envoy, Venus Express, was launched in November 2005. During the eight-year mission, the spacecraft's swooping orbit brought it low over the cloud tops and revealed big variations in the sulfur dioxide content, suggesting that the volcanoes were still active. Its fuel exhausted, Venus Express was purposefully destroyed in the atmosphere in early 2015.

A Japanese space probe called Akatsuki, launched towards Venus in 2010, looked lost after a fault caused it to fly past the planet. But five years later, mission controllers managed to rescue it and put it into a new, more elongated orbit where it began to survey the atmosphere.

Two NASA missions to the outer planets also gathered data on Venus as they flew past to get a gravitational boost on their long journeys. Galileo shot past on its way to Jupiter in February 1990, taking pictures, measuring dust, charged particles and magnetism, and making infrared studies of the lower atmosphere. Saturn probe Cassini made two flybys in April 1998 and April 1999 when it looked for, but failed to spot, lightning in the clouds.

The Trouble with Landers

Current proposals for future Venus missions are focusing on orbiters and a new generation of balloons and aerial vehicles. Experts see too many difficulties in sending a lander to explore the surface like the Martian rovers. As planetary scientist and Venus expert Dr. Colin Wilson of the University of Oxford explains: "The issue is the heat, because silicon electronics simply don't work at these temperatures. There are studies into building a new kind of electronics using silicon carbide — this is of interest also for use inside car engines and jet engines — but even if you sort that out, you still have the problem of how you are going to power a probe on the surface. Although Venus is closer to the Sun, only one or two per cent of the sunlight at the cloud tops reaches the surface and so solar panels are completely impractical. Radioactive power sources have been suggested, but this would make the mission both expensive and difficult."

Two proposals to explore Venus are on a shortlist of five Solar System projects currently being considered for the next round of NASA's Discovery Program, missions that could launch in the early 2020s. One, called DAVINCI (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry and Imaging) is being studied by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. It is an entry probe designed to study conditions between the dense cloud tops and the surface. "It will have much more modern and accurate instrumentation than previous probes," says Wilson. "All their temperature sensors failed in the lower atmosphere so we have hardly any data about atmospheric processes near the surface. DAVINCI is really going to give us a much better understanding of the deep atmosphere of Venus, in particular of its chemistry." The other proposal, from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, is for a new orbiter called VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography and Spectroscopy) that aims to produce radar maps of the planet in much higher resolution than before. It has strong European support, including for a French-German infrared camera that will look for hot volcanic material on the surface.

Looking Further Ahead

But a further attempt to get a new spacecraft to Venus will come with a UK-led proposal to ESA for a mission called EnVision. The probe will be another orbiter with advanced radar to detect tiny changes in surface features, at centimeter scale, that could confirm lava flows or similar surface deformation. Looking farther ahead, Venus scientists are keen to see a new generation of balloons or airships to taste the planet's atmosphere. It has been suggested that simple microbial life might exist in the cloud tops, though this is pure speculation. One advanced concept being prepared in the US is for a delta winged aircraft called VAMP (the Venus Atmospheric Maneuverable Platform) to be dropped by an orbiter into the clouds. Once in the atmosphere it would switch to flight phase, spending up to a year maneuvering between the upper and mid cloud layers, gathering data to send back to Earth. During the Venusian day, it would fly in the higher atmosphere, charging its batteries from the sunlight, before dipping to lower regions again at night.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Paul Sutherland is a space journalist, and the author of Where Did Pluto Go? Each month he reports on the latest space research in BBC Sky at Night magazine.

Copyright © Immediate Media. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical without permission from the publisher.

/

/